Why the “Secret” Coast? Well, because most people think of Canada’s colonial history in terms of the English and the French. But there is a whole period of history that is unknown to most Canadians – and many of those events took place here on Vancouver Island. Here in the Pacific Northwest coast, the Spanish were big players: they were actually the first to arrive and make contact with the indigenous Nuu-chah-nulth.

The Secret Coast will become a book that I (Jackie) will both write and photograph. I envision a format very similar to that of my best-seller The Wild Edge. The text will weave the narrative of our upcoming one-month wilderness expedition with our discoveries of the history of this region. Now wild and nearly entirely uninhabited, the Secret Coast was once a hive of activities: comings and going of Spanish and British and American sailors, all vying for trading privileges with the Nuu-chah-nulth and hoping to lay claim to these lands in the name of their countries.

The Nuu-chah-nulth had (and have) inhabited these lands since “time immemorial” (In archeological terms, that means at least for 5000 years, the oldest radiocarbon dates attesting to their presence – but probably for much much longer). In 1774, the first European ship to make contact with the Nuu-chah-nulth, the Spanish frigate Santiago, sailed into Homais Cove (on the Hesquaht Peninsula, near the southern entrance to Nootka Sound). Conditions were rough: the Spanish made contact and traded with the Nuu-chah-nulth from their ship, but never set foot on shore.

Four years later, the famous British navigator Captain Cook sailed into Nootka Sound and came ashore at Yuquot, which he renamed Friendly Cove – in reference to the Nuu-chah-nulth inhabitants who greeted him. The resulting conflict (Spain insisting “We got there first!” while Britain countered “But you never set foot on shore!”) eventually culminated in what is now known as the Nootka Crisis: by the early 1790s, Spain and Britain nearly came to war over these lands. (More about the Spanish in the Pacific Northwest in an upcoming blog post).

Meanwhile, the Americans were out and about. Cook had made it generally known that great riches were to be made selling the furs from the coast over in China. From the late 1780s on, American ships were also active in this region, at times coming into conflict with the Spanish.

After resolution of the Nootka Crisis, the Spanish gave up their claims to the territories here. The Americans and the British were now the main foreign visitors to the coast – although their relations with the Nuu-chah-nulth people gradually deteriorated. In 1803, the Nuu-chah-nulth captured the American ship the Boston, killing all on board except for two, who they enslaved for over two years.

Then 1811, John Jacob Astor’s ship the Tonquin, sailing from New York, was captured by the Nuu-chah-nulth near what is now Tofino. This was in part in revenge for the burning of their village of Opitsaht by the American Captain Robert Gray nearly two decades earlier. This final conflict deterred both the Americans and the British, and for the next half-century the Nuu-chah-nulth people were left alone by foreign explorers.

Dave and I are really excited about our upcoming adventure, and our chance to visit the historically significant sites where these events – and many more – occurred. Our focus is this period, 1774 to 1811, but there are also some very interesting happenings after that period, too – from shipwrecks to bombings to chainsaw-gardening – that I will write about too!

.

We are very pleased to announce that the

We are very pleased to announce that the

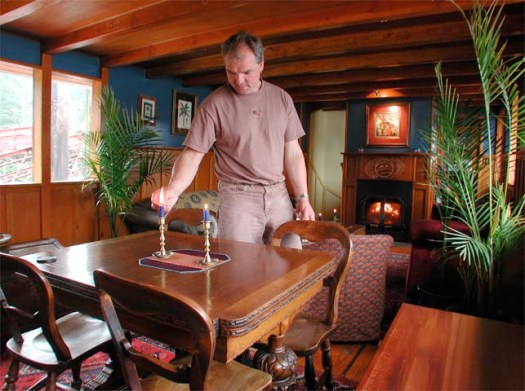

Cougar Annie died in 1985 at the age of 97, and her long-term friend and supporter, Peter Buckland, who met her while prospecting in the area, purchased the property from her. By then, most of the garden had been consumed by the rainforest. But, in a project that has been on-going since that time, Peter has year-by-year beaten the rainforest back (his term for it is “chainsaw gardening”), uncovering a wealth of heirloom plants along the way: from flower bulbs that had been dormant but alive under the shade of the salal for decades, to giant rhododendron trees that became part of the rainforest structure themselves.

Cougar Annie died in 1985 at the age of 97, and her long-term friend and supporter, Peter Buckland, who met her while prospecting in the area, purchased the property from her. By then, most of the garden had been consumed by the rainforest. But, in a project that has been on-going since that time, Peter has year-by-year beaten the rainforest back (his term for it is “chainsaw gardening”), uncovering a wealth of heirloom plants along the way: from flower bulbs that had been dormant but alive under the shade of the salal for decades, to giant rhododendron trees that became part of the rainforest structure themselves.

I’m super-happy to announce that

I’m super-happy to announce that

Lucky for us we have a pair of Feathercraft folding kayaks! Each boat fits into a big backpack. These are excellent kayaks: skin-and-frame design (like the original Inuit kayaks), but with the skin made of nylon cordura fabric and hypalon rubber (the same stuff Zodiacs are made of), and the frame made of aircraft-grade aluminum.

Lucky for us we have a pair of Feathercraft folding kayaks! Each boat fits into a big backpack. These are excellent kayaks: skin-and-frame design (like the original Inuit kayaks), but with the skin made of nylon cordura fabric and hypalon rubber (the same stuff Zodiacs are made of), and the frame made of aircraft-grade aluminum. These Feathercrafts are extra-special, because they are not even made any more. I have paddled other brands of folding boats before, and honestly, they don’t perform like kayaks at all – they are more like pointy rafts. (What is so special about a sea kayak is that you lock your legs and hips into them – so it is not like sitting in a boat it all. Rather, it is like adding an extension to your body – you maneuvre it with your whole body. That is why and how you roll a sea kayak: you must use your whole body to do it). I’ve paddled my Feathercraft all over the world: Australia, New Zealand, French Polynesia (photo to left from 20+ years ago!), Mexico, and both eastern and western Canada. I’ve had it in some pretty big seas – I have even Eskimo-rolled it! These are

These Feathercrafts are extra-special, because they are not even made any more. I have paddled other brands of folding boats before, and honestly, they don’t perform like kayaks at all – they are more like pointy rafts. (What is so special about a sea kayak is that you lock your legs and hips into them – so it is not like sitting in a boat it all. Rather, it is like adding an extension to your body – you maneuvre it with your whole body. That is why and how you roll a sea kayak: you must use your whole body to do it). I’ve paddled my Feathercraft all over the world: Australia, New Zealand, French Polynesia (photo to left from 20+ years ago!), Mexico, and both eastern and western Canada. I’ve had it in some pretty big seas – I have even Eskimo-rolled it! These are  So we will be able to transport the kayaks

So we will be able to transport the kayaks